The Energy Consulting Group

Business strategy for upstream oil and gas producers and service companies

Oil and Gas Decline Rates: Accelerated Decline

Our research indicates that decline rates have increased for oil and gas fields around the world. A major implication of this trend is the E&P industry is having to work harder than in any past period just to maintain production, much less grow it. More specifically, our work on oil supply fundamentals illustrates that the higher decline rates are offsetting to a large extent the strong supply response to higher prices. This response will be especially notable in 2008 and 2009. This is not to say net production growth (new capacity less production declines for fields already in service) will not exceed demand growth. In fact, it likely will, leading to moderate increases in spare capacity. More problematic is post-2009, when annual new capacity added each year is currently on track to be substantially less than in 2008 and 2009. Given that decline rates are likely to stay relatively high, we conclude the market is at real risk of returning to the situation it faced in 2004-2006, i.e. escalating prices and significant exposure to event risk.

The Evidence

We

have come across many anecdotal stories of decline rates increasing

with our industry contacts citing new technologies, shifting

project mix, such as more deepwater fields, and strong growth in

rate acceleration projects. However, we believe some of the best

evidence that decline rates are accelerating comes from our

analysis of what is happening in North American natural gas fields,

and from the work we have done on net capacity additions to global

oil supply.

North American

Gas

Presented below are the results of work we did on

the Ignacio Blanco (IB) field in New Mexico, the Hugoton field in

Kansas, and the Jonah field in Wyoming. These are significant

because they are three of the largest gas fields in the

US..

.

.

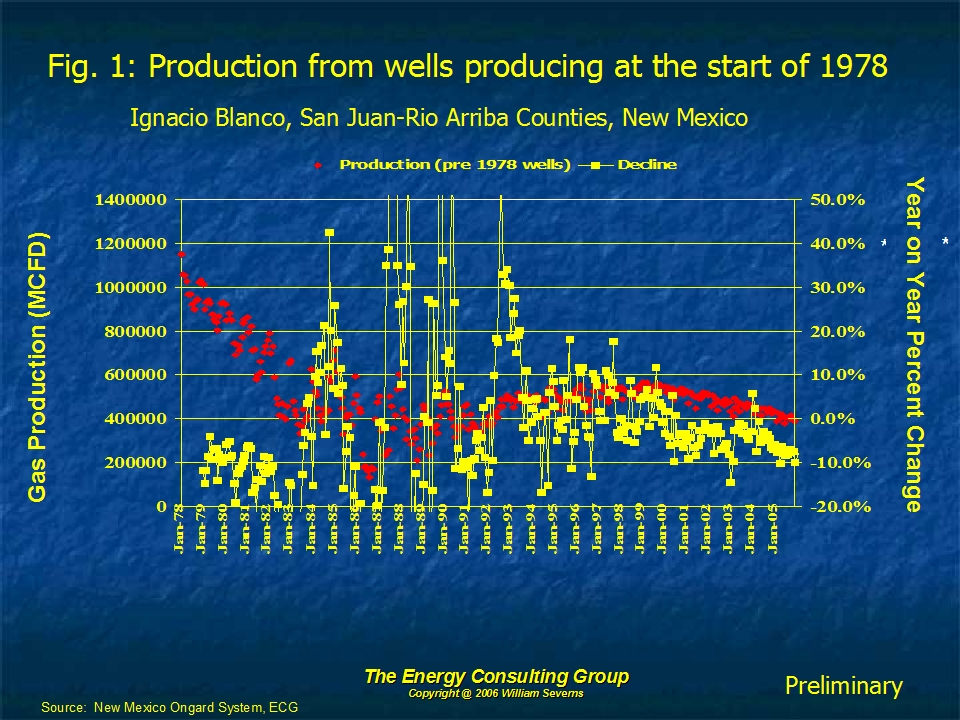

Figure 1 for the Ignacio Blanco field documents how wells

producing since the late 1970's have undergone profound changes in

their decline profile over the past 25 years. During the last

period of unrestricted production, the late 1970's and early 80's,

these wells were declining on the order of about 10 percent per

annum. With the emergence of industry wide surplus capacity, known

affectionately as the gas bubble, and which ran from the mid-1980's

to the early 1990's, decline rates fell off dramatically in the

face of severe allocation/proration restrictions on production. As

the gas bubble began to deflate in the mid-1990's, the restrictions

were eased and operators began to produce gas wells at full

potential, resulting in decline rates resuming and eventually

matching the rates of the early 1980's. The

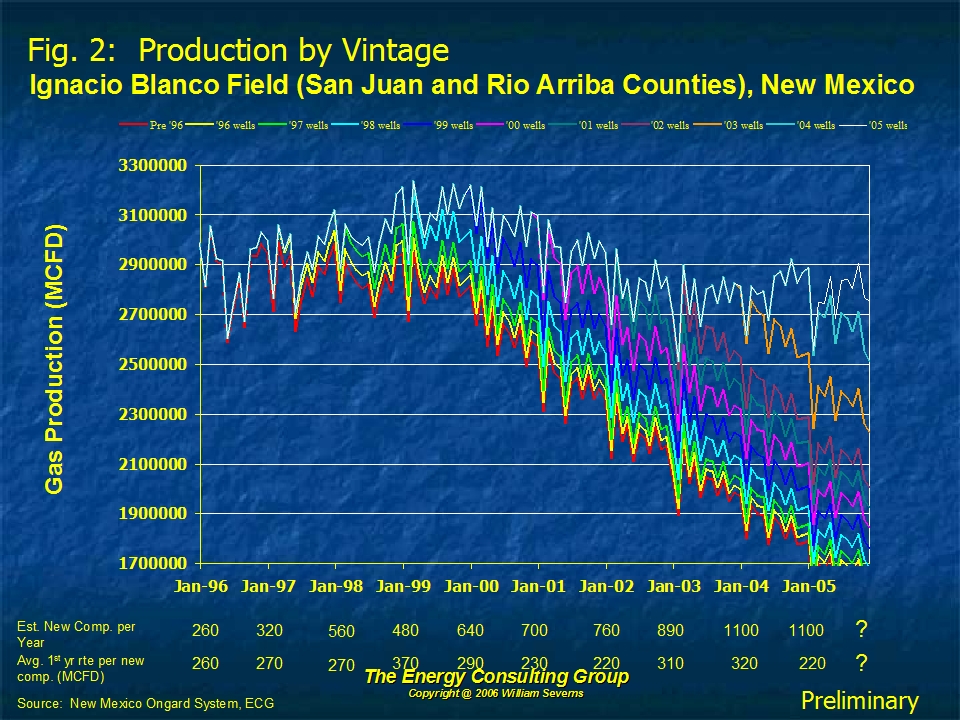

result, presented in Figure 2, is total

output from IB has been flat to declining despite a quadrupling of activity, as measured by the annual

number of new well completions over the last ten

years.

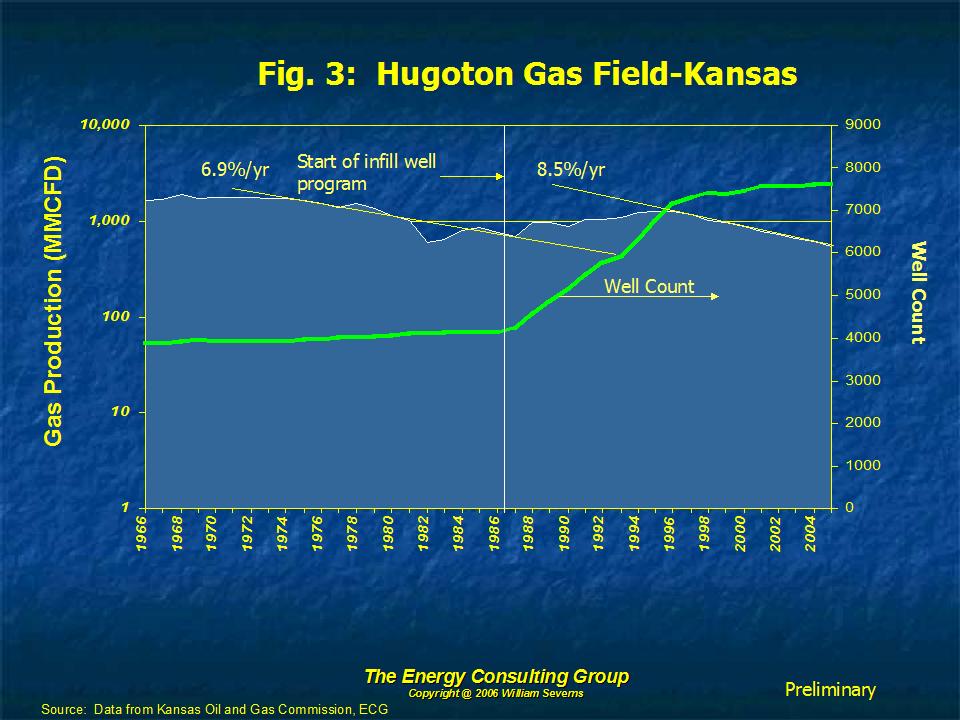

The Hugoton production slide (Figure 3) tells a

similar story in terms of aggregate decline accelerating on the

other side of the bubble period. The field wide decline rate moved

from about 7% per annum to 8.5%. We attribute most, if not all, of

this increase to more aggressive field management practices, the

most notable of which is an infill drilling program that took place

at Hugoton starting in the late 1980's, essentially doubling the

number of straws draining the same area. Such programs usually have

two justifications:

1) Higher ultimate recovery due to pockets of oil and gas being

tapped by the infill well

2) Higher production rates

However, these benefits generally come at the

cost of the higher rates more rapidly depleting the field,

resulting in a higher decline rate. In essence, the production

increase is greater than the reserves boost.

To illustrate higher decline rates are not a "old field" phenomena,

we also looked at several of the "new" fields, including the

Barnett shale, Piceance Basin developments, deep East Texas tight

gas fields, and the Madison, Jonah and Pinedale fields in the Green

River Basin in Wyoming. It is our conclusion that these fields are

experiencing declines at rates higher than typical for gas fields

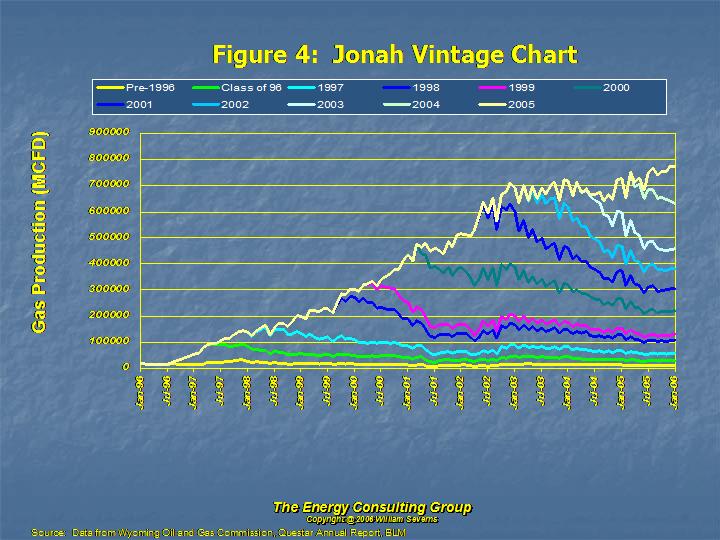

developed in the past. Figure 4 presents a production profile for

the Jonah field. Note, that it is declining about 20% per year, or

about twice the decline rates of the older fields.

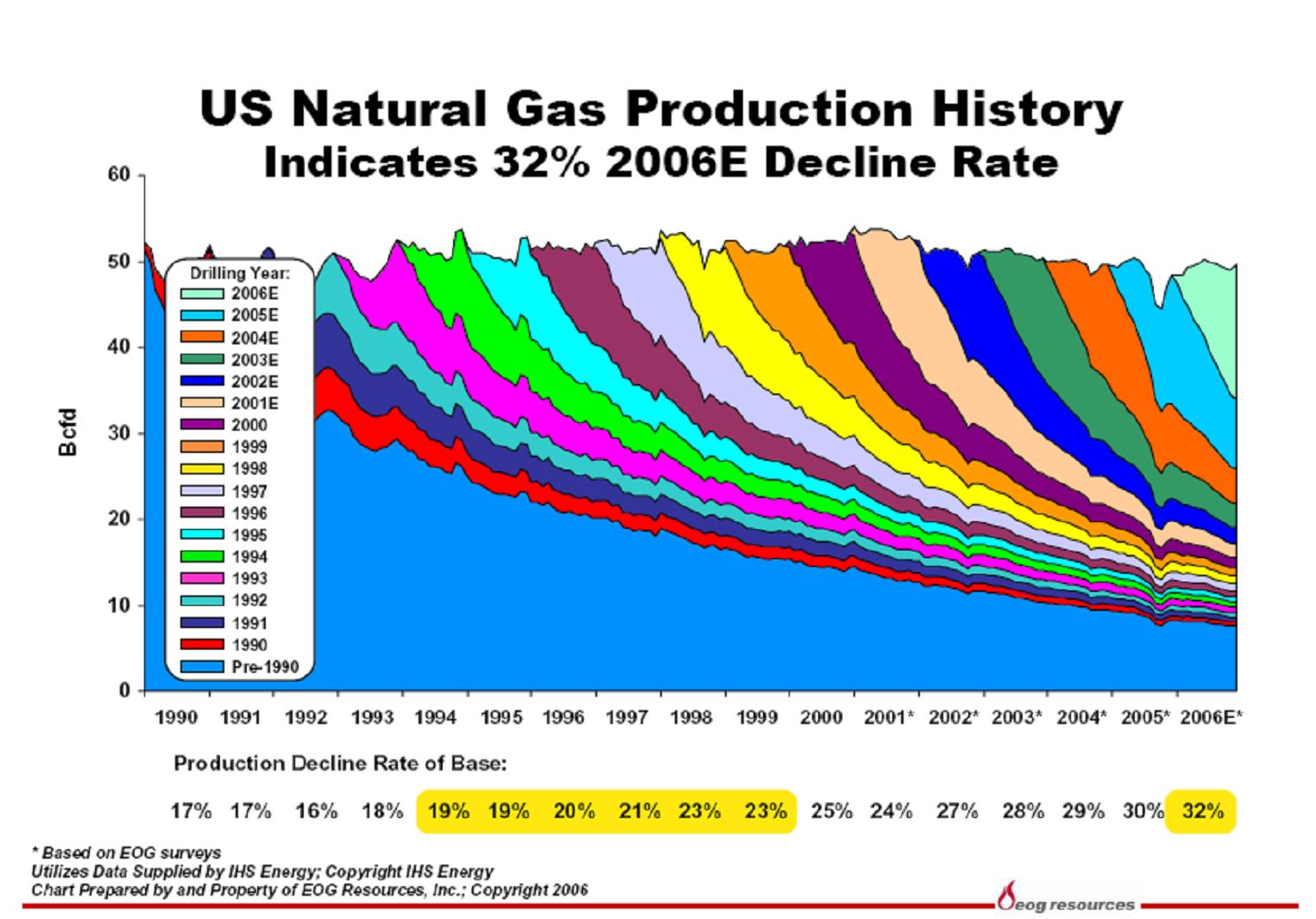

Our findings are similar for several other of the large, recently developed gas fields we have studied, suggesting this is a widespread phenomena. Many of the new fields produce from tight reservoirs. Wells in such settings typically have very high rates of initial decline, as much as 80% the first year, though the decline moderates in subsequent years. This is compared to the 10% or so typically experienced in "conventional" fields. Given the rapidly growing percentate of wells drilled in tight, nonconventional settings, it would be logical to conclude that they are contributing to a higher rate of decline. Indeed, this factor,combined with accelerating decline rates in older fields, should mean increasing aggregate decline rates. This conclusion is appears borne out by work done by EOG, summarized in the chart below.

Summary-Drivers of Accelerated

Decline

These North American gas field examples illustrate

the fundamental thesis of our argument: higher rates of average

decline are occurring and have three drivers

1) Oil and gas technology is advancing rapidly This allows firms to produce at higher rates for longer, without a commiserate increase in reserves; in a related vein, higher prices allow firms to invest more initially to produce fields faster, meaning more wells, among other actions, to drain the same volume.

2) A key set of assets have higher

decline rates than more traditional fields In the case of US

natural gas, it is the growing market share of tight gas fields.

For oil, output from deepwater fields is one of the fastest growing

segments of the upstream industry. Given their relatively high

upfront capital costs, one of the prime design goals it to front

end load recovery, meaning higher initial rates at the expense of

steeper declines once fields come off plateau.

3) Applying more aggressive production

strategies An obvious example infill wells

Our field level analysis illustrates these factors are impacting

the industry. Since these drivers apply as much to oil fields as

gas fields, we would expect to see higher rates of decline in these

fields as well. In fact, history matching production derived from

the ECG's oil project database with production volumes reported by

the EIA and IEA shows this to be the case. The analysis indicates

aggregate oil field decline rates are approximately 1 to 2

percentage points higher now than in the past.

However, the interesting question is not whether

the phenomena is occurring, but whether the industry can out run

this higher pace of depletion. For North American natural gas, we

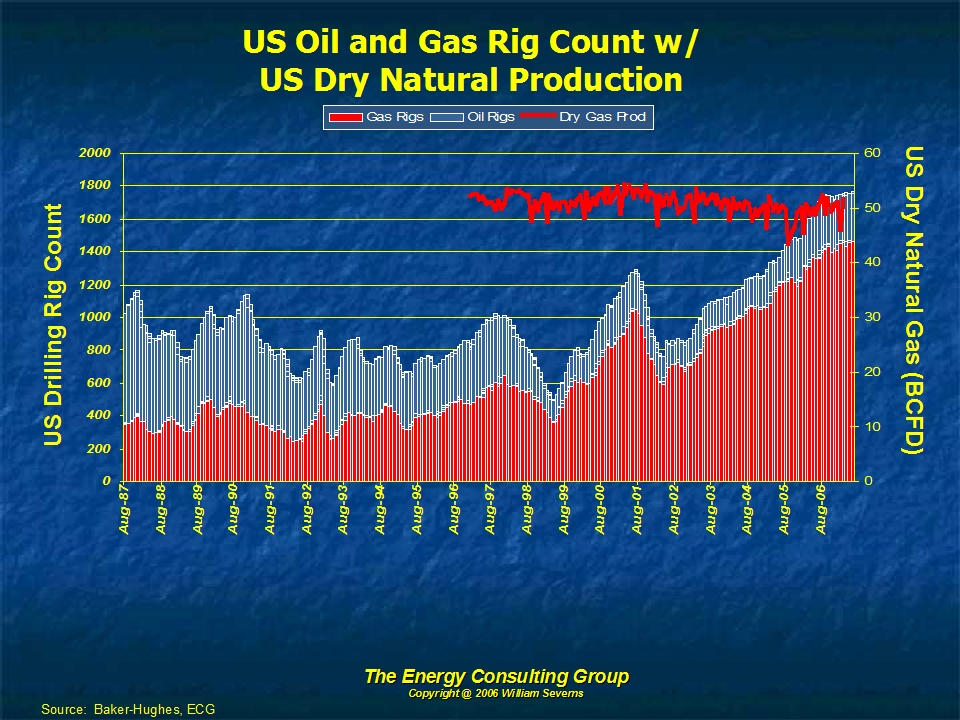

think it will be difficult. Indeed, despite the number of rigs

drilling for natural gas tripling over the past ten years,

aggregate production volumes struggle to rise above levels attained

as recently as two- three years ago.

For oil fields, our analysis indicates that while the industry will be able to achieve some increase in spare oil production capacity over the next 3 years, in the longer term the same drivers impacting US natural gas production, will make it increasingly difficult for the industry to outrace the higher rates of oil decline.

The Energy Consulting Group home page

|

E&P News and Information Scandinavian International and National International Energy

Agency Department of Trade and Norwegian

Petroleum Ministry of Industry

and E&P Project Information |

|---|